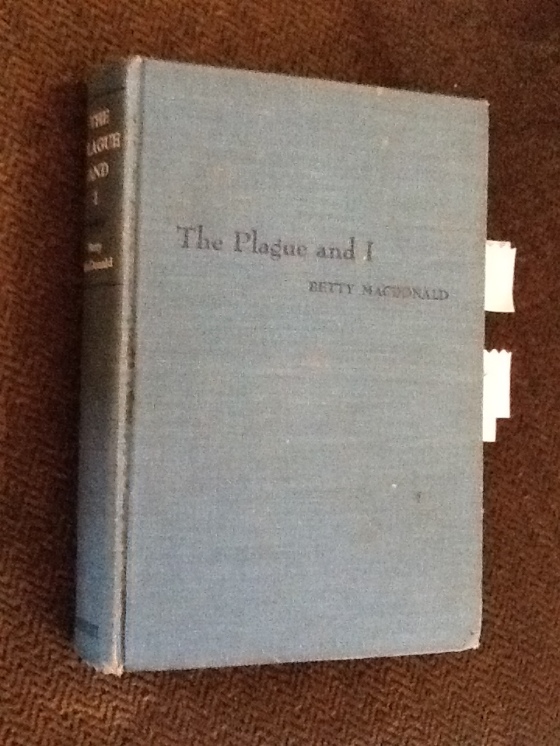

When I read a book, I am an underliner. When I am finished, I will go back and copy down the things that I need to follow-up on or that I really want to remember. A few weeks ago, I finished a book on the history of tuberculosis. One of that book’s notes: “get Betty MacDonald’s The Plague and I.” Unfortunately for the world, The Plague and I has been out of print since 2000. However, with the awesome online opportunities that we are now afforded, I found a 1948 hardback copy on ebay for a reasonable $7.99. Got it. Read it. So delightful!

When I read a book, I am an underliner. When I am finished, I will go back and copy down the things that I need to follow-up on or that I really want to remember. A few weeks ago, I finished a book on the history of tuberculosis. One of that book’s notes: “get Betty MacDonald’s The Plague and I.” Unfortunately for the world, The Plague and I has been out of print since 2000. However, with the awesome online opportunities that we are now afforded, I found a 1948 hardback copy on ebay for a reasonable $7.99. Got it. Read it. So delightful!

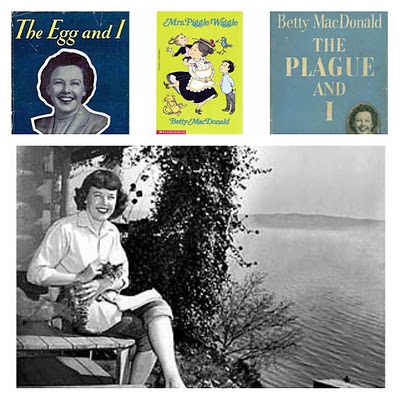

Let’s start with the author. I knew of Betty MacDonald mostly from her Mrs. Piggle Wiggle series of books. Ali was a big fan of Mrs. Piggle Wiggle, a sweet old lady who lived in an upside down house in a neighborhood crowded with children. Mrs. Piggle Wiggle possessed a dresser that was full of cures for misbehaving children. The dearly departed Mr. Piggle Wiggle (who was a pirate!) bequeathed these cures to his widow. Among them were The Selfishness Cure, The Tattletale Cure, The Crybaby Cure… These stories were the bedtime tales that Betty entertained her children and other relatives with. Lucky them.

For adults, besides The Plague and I, Betty MacDonald also wrote three other autobiographical books: The Egg and I, Onions in the Stew, and Anybody Can Do Anything. All of her books were published between 1945 and 1957 as, sadly, in 1958 at the age of 49, she died of uterine cancer.

Back to The Plague and I. I didn’t know what to expect. I knew this was a first person account of being in a tuberculosis sanatorium in the 1940s. That was enough for me! From the start, however, the reader is clued in that there could be some humor here. In the book’s dedication, she thanks her doctors who “without whose generous hearts and helping hands, I would probably be just another name on a tombstone.”

The sanatorium cure was quite something. Patients first were placed in rooms where they laid flat for weeks. They could not speak, could not get out of bed, could not read. The cure theory was lung rest, and anything besides perfect stillness would tax the lung and delay the healing. It seemed quite awful, but Betty pushes that aside by showing how one can cope in such a situation. Her way involved covertly chatting with her roommates, breaking rules, and ascribing hilarious names and back stories to the staff.

The connections that she develops while in the sanatorium are strong. Her first roommate, Kimi, is a tall, intelligent, Japanese-American girl. Before tuberculosis made her an outcast, Kimi felt ostracized by her community because of her height. Kimi handles her situation with unnatural calm. This intrigues Betty. When Betty cannot believe how peacefully Kimi can conform to the bedrest, Kimi explains that she uses the time to visualize how she will torture the nurses. That is the start of a great friendship. Later in the book, after the reader is introduced to a series of wittily drawn characters, Betty reflects that after her stay was over, her litmus test for new acquaintances was “Would she be pleasant to have t.b.with?”

The book blends this humor with, what I think is, an accurate portrayal of what such a life experience would have been like. Eerily, at this sanitarium, there was a separate home for the children of some of the patients. In many case, two parents would be infected and there would be no place for the children to go. Sometimes, however, neither parent made it out.

She describes the noises of the staff and patients. She recounts the procedures that would be conducted to work the cure. This was a time before antibiotics, so healing meant fresh air, lots of food, and invasive procedures like pneumothorax. The pneumothorax involved air being forced into the chest in order to collapse the lung and allow it to rest and heal. This would have to be repeated regularly. Healing was monitored with regular chest x-rays.

Photo from: http://www.lung.ca/tb/images/

As progress was made, the patient had more freedoms. Each phase of Betty’s stay is riddled with ridiculous rules and people. The section of the book detailing occupational therapy – where patients receive instruction on how to make kitschy crafts that may be their source of income in the future – is hysterical. Betty ascribes the family name for these crafty items – “toecovers”: defined as a useless gift.

Betty was lucky as her time in the sanatorium lasted only nine months. She writes of her release, and the months spent trying to regain normalcy. It was not easy or completely possible. The new her was labeled with her disease and the prejudice that came with that.

But what saw her through was this:

“In addition to good health, my family possessed a great capacity for happiness. We managed to be happy eating Grammy’s dreadful food or Mother’s delicious cooking; in spite of cold baths and health programs; with Grammy’s awful forebodings about the future hanging over our heads; in private school or public; in very large or medium-sized houses; with dull bores or bright friends; with or without money; keeping warm by burning books (chiefly large thick collections of sermons, left us by some of the many defunct religious members of the family) or anthracite coal in the furnace; in love or just thrown over; in or out of employment; being good sports or cheats; fat or thin; young or old; in the city or in the country; with our without lights; with or without husbands.”

Betty had the capacity for happiness even when the family’s gift of good health failed her.

You would definitely pass my TB friend test! Thanks for sharing this.

I loved Mrs PIggle Wiggle when I was a child. Didn’t realize she had written others, might have to check them out. This one looks fascinating. Quite a feat to stay optimistic through that sort of health care!

I was a huge fan of the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle books as a kid. This one sounds fascinating.

It’s my understanding “Kimi”, the roommate in The Plague and I, is (was) actually the budding psychologist and author Monica Sone–who wrote a wonderful book of her own titled Nisei Daughter.

Interesting! I did not know that!

I recently discovered this, and immediately checked out Nisei Daughter from the library. Most of the book focuses on the author’s childhood in depression-era Seattle, and later internment during WWII. However, she devotes several pages to her tuberculosis sanitarium stay. She refers to the institute as “North Pines”,while MacDonald calls it “The Pines”. Sone’s name for MacDonald is “Chris Young”: a quote from her book: “Chris, in the third corner, with her fluff of copper bright hair, laughed easily and her crisp humor took the drabness out of our routine life.”

The sanitarium was named Firlands in real life, and is now home to a Christian school. My husband and I visited it one day (we live between Seattle and Vancouver BC) so I could walk in MacDonald’s footsteps. I was able to identify what must have been the sleeping porch MacDonald describes in The Plague and I.

On the Olympic peninsula outside of Port Townsend there’s a lane called Egg and I Road, named for the location of MacDonald’s Egg and I setting. We drove up and down but were never able to pinpoint the actual chicken farm area.

Have you read Anybody Can Do Anything? I love all (too few!) of MacDonald’s books, but I can never decide which is my favorite: The Plague and I, or Anybody Can Do Anything.

It’s nice to meet other MacDonald fans.